By Patrick Dobyns, Editor

It’s something that we’ve all heard growing up; “You’re lucky to have been born in America.” For myself, it was repeated to me ad nauseum in my elementary and middle school history classes, and even though those exact words tapered off in high school, the message was still there. At the time, the message was convincing. We’re told about our institution of democracy, how it was born in opposition to a tyrannical monarchy, how people elsewhere in the world don’t have the same rights and freedoms that we do and so on…

Like I said, we’ve all heard it before, and you don’t need me to repeat it. And I won’t deny it, either. A republican form of government is certainly preferable over totalitarian regimes, and there are certainly places in the world where a person’s rights take something of a backseat to the national interests of their country. But saying we’re lucky isn’t accurate, and it isn’t safe. To see why, we can look back to Germany’s first foray in democracy, what eventually became known as the Weimar Republic.

Near the end of the first World War, in 1918, the German people were tired of the fighting, and as the Kaiser’s government refused peace terms from the Allied Powers, the people rebelled. In November, the Kaiser was forced to abdicate the throne, an armistice was signed, and a new Republic was declared within two weeks. Although the government was divided, a written constitution was officially adopted in August of 1919.

The establishment of this new state was not without its troubles, however. Between the proclamation of the republic and the adoption of the constitution, many far left and Communist groups opposed the more moderate parties which had originally seized power. The Communists rose up in their own rebellion, using workers strikes to try and start their own governments. While the uprisings were put down, many of the sentences were lenient, and divisions within the new government remained.

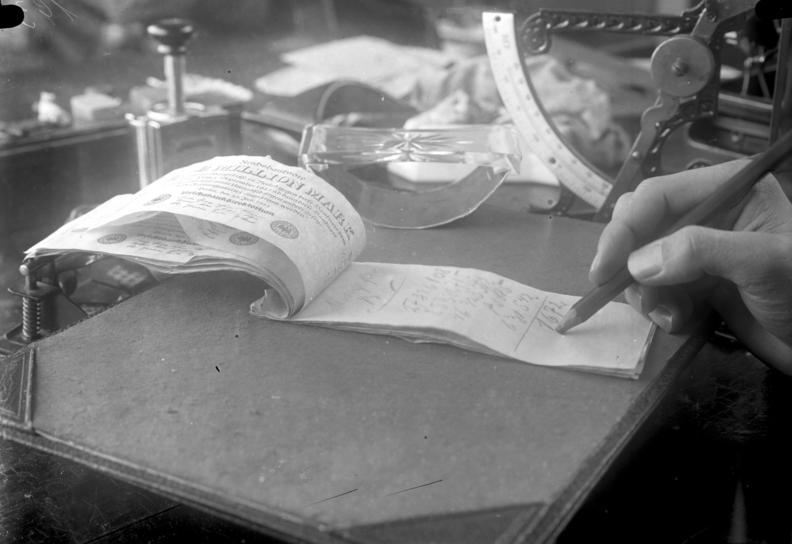

In addition to political divides, the situation in Germany was made even worse by an economic crisis, spurred on by a combination of the loss of German overseas colonies, a continued Allied blockade of German ports until 1919, and harsh reparations demanded by the Treaty of Versailles. While unemployment was kept largely under control, inflation rates had skyrocketed, peaking in 1923. To many Germans, the Capitalist ideology of the new Republic was to blame for their financial woes, and the socialist and communist parties saw a substantial increase in membership.

To others, the Allied powers were solely responsible, and a popular theory circulated that Germany’s loss during the Great War was not its own fault, but due to the actions and subversions of foreign immigrants, corrupt officials, minorities, and the far left. These sentiments fueled several far right movements, many of which became prominent among army veterans. They believed that the rebellions that had occurred while German troops were on foreign soil had been a “stab in the back”.

Over the following years, both groups would use violence to attempt to seize political power; a prime example of this being the Kapp Putsch, led by General von Lüttwitz, who wished to restore the pre-revolutionary government and the Ruhr uprising, a series of labor strikes that workers used to try to seize power in the heavily industrialized Ruhr region. Both attempts were ultimately put down by the Reichswehr (the German National Army) and the Freikorps (German mercenary companies). When elections were held for the Reichstag (German Parliament) in 1920, the center-left coalition lost 125 seats to other parties of both sides.

Despite this, Germany started to stabilize during the latter half of the 1920’s. The introduction of a new currency and the enactment of the Dawe’s Plan (an international economic plan which set up staggered payments of German reparations and foreign loans to Germany) stabilized the German economy and reduced the hyperinflation that had caused food prices to soar. While domestic policy saw some inconsistency under frequently rotating Chancellors, foreign policy remained consistent and the nation even gained standing in the League of Nations that was established after the war. A cultural renaissance, mirroring the United States’ “Roaring Twenties” and influenced by other cultural movements throughout Europe, exploded in German society. It was a brief golden age—one that would be brought down when the New York Stock Exchange collapsed in October of 1929.

This is the part of the story that many more are familiar with. Adolf Hitler, who had taken leadership of the National Socialist German Workers (Nazi) Party, and had led the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, found himself leading the second largest party represented in the Reichstag, with 19% of the seats. The Communist Party had also been gaining seats. As political tensions became even more extreme, the chancellors of the early 1930’s were unable to pass measures through the Reichstag, and so resorted to Presidential Decrees. In January of 1933, Hitler was elected Chancellor and immediately set out to suppress the leftist parties of Germany. When the Reichstag caught fire in February, Hitler used the event to blame foreign communists and pass emergency measures, which suspended rights and protections for all Germans.

In March, Hitler enacted the Enabling Act, essentially dissolving the Reichstag, granting all powers of the state to the Chancellor’s cabinet, and making all other political parties illegal. In August, 90% of German voters approved to giving Hitler the Office of President, furthering his power, and leading to the complete dissolution of the Reichstag in November.

We are not lucky to have been born in the United States. Yes, we have it better than elsewhere. Yes, we have rights and liberties others don’t and have a chance to make our voices heard in elections and protests. But we are not lucky. We are protected by our Constitution, but it is not guaranteed. We are not safe from tyranny by virtue of our country. It can go wrong.

We saw it go wrong with the fall of the Weimar Republic, born rebelling from a monarchy that did not represent their interests in August of 1919 and gone in August of 1934. Economic crisis and political division led to a populist demagogue seizing power from and undermining democratic institutions, ruling through decree rather than consent, and stripping the rights of the citizens he claimed to protect.

Saying we’re lucky isn’t just inaccurate, it’s dangerous. There’s an implication in that statement that, no matter what, we have our rights guaranteed by virtue of being born here, by virtue of our Constitution. None of that is guaranteed, though. The rights we have do protect us, but if we don’t protect them in turn, they mean nothing. Rights can be taken away and have been taken away. A democracy is not inherently safe. We need to do our part to make it safe.