By Patrick Dobyns, Editor

Recent news has been filled with, among other things, the use of the United States National Guard against US citizens. Earlier this year, protests in Los Angeles prompted Donald Trump to mobilize the Guard to suppress participants. Last month, National Guard members were put in a more direct role of law enforcement in Washington, D.C., with Trump inaccurately boasting that the city had gone a week without a murder for the first time in over a decade; Washington D.C. had, in fact, seen eleven days without a murder in January of this year. The use of military troops for civil law enforcement sets a dangerous precedent, leading towards self-governance being aggressively undermined by federal power grabs. I could bring up the times in world history where this exact thing happened, but this time, I think I’ll keep things more local and closer to what we are seeing now.

In 1970, the United States was in the midst of the Vietnam War; this being the first conflict brought to the American people via televised broadcast, the horrors of war became much better understood by the general public. Understandably, this upset a great number of people. A counter-culture movement became prevalent across the country, with subcultures such as Yippies and Hippies staunchly anti-war. While there were still a good number of people who supported US actions in South-East Asia, the clashes between these viewpoints made this a particularly volatile time in the States.

President Richard M. Nixon had gained a reputation of being particularly opposed to counter-culture movements, appealing to what he called the “silent majority” during his campaign, which he described as non-vocal social conservatives who shared his disdain for anti-war protestors. Giving credit where it is due, President Nixon was making attempts to pull out of Vietnam, seeing it as a war that America could not win. Despite this, peace talks never seemed to lead to any agreements, and “Vietnamization” (the gradual replacement of US troops with South Vietnamese soldiers) was not proving fruitful. However, as he was pulling troops out, he still had movements strike various points along the Ho Chi Minh trail and into the Khmer Rouge, the communist forces of neighboring Cambodia.

When North Vietnamese forces entered Cambodia en masse at the request of the Khmer Rouge, Nixon announced a retaliatory campaign into Cambodia. To many Americans, this represented an expansion of the war rather than a withdrawal. It was no surprise when protests erupted across the nation the next day, May 1, 1970—particularly on college campuses.

One such campus was Kent State University, in Northeastern Ohio. Kent State had experienced years of anti-war protests, none of which had been violent. The first Vietnam War protests were held that day, attracting 500 students for the first demonstration and 400 for the next. Both protests dispersed peacefully by 1 pm and 3:45 pm, respectively.

The widespread protests seemed to have angered Nixon just as much as the Viet Cong and Khmer Rouge had. An interview with The New York Times that same day prompted a response, in which Nixon called the protestors “bums,” and he accused them of blowing up campuses and burning books. “Get rid of the war, there will be another one,” he said. That night did see violent protests, but not at the University.

The Akron Beacon Journal reported that five police officers were wounded by a group of rioting anti-war protestors outside of a bar. The crowd did contain students, but it also included bikers and transients. Rocks were thrown, both at police and at storefront windows in the downtown area. After a crowd of 120 people gathered, the Mayor of Kent, LeRoy Satrom, declared a state of emergency and ordered all of the bars in town to be closed, which only increased the tensions between law enforcement and the rioters. The rioters were dispersed with tear gas early in the morning, driving them out of the downtown area.

The riot threw the town of Kent into an uproar. Business owners and officials reported receiving threats, and rumors began to spread that students were planning a more coordinated and destructive attack on the campus — possibly by spiking , or that students were planning to spike the town’s water supply. One rumor even spread that students were digging tunnels under the town to blow up city buildings. None of these rumors were ever substantiated, but a fire that was set at the campus’ ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) building only fanned the flames of paranoia — despite an FBI investigation concluding that students were most likely not the culprits of the arson.

Just before the arson, Mayor Satrom called for Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes to send the Ohio National Guard to break up the protests. The request was granted and the Guard arrived at 10 pm, beginning to detain students using tear gas and bayonets.

The next day, Satrom addressed the town, stating that he was going to “eradicate the problem.” He claimed the students were “worse than the brown shirts and the communist element” and “the worst type of people that we harbor in America.” Despite this verbal attack, students from Kent State came to help with clean-up efforts, with mixed reception. Another non-violent protest was held on campus that night, and later dispersed again by the National Guard with tear gas and bayonets.

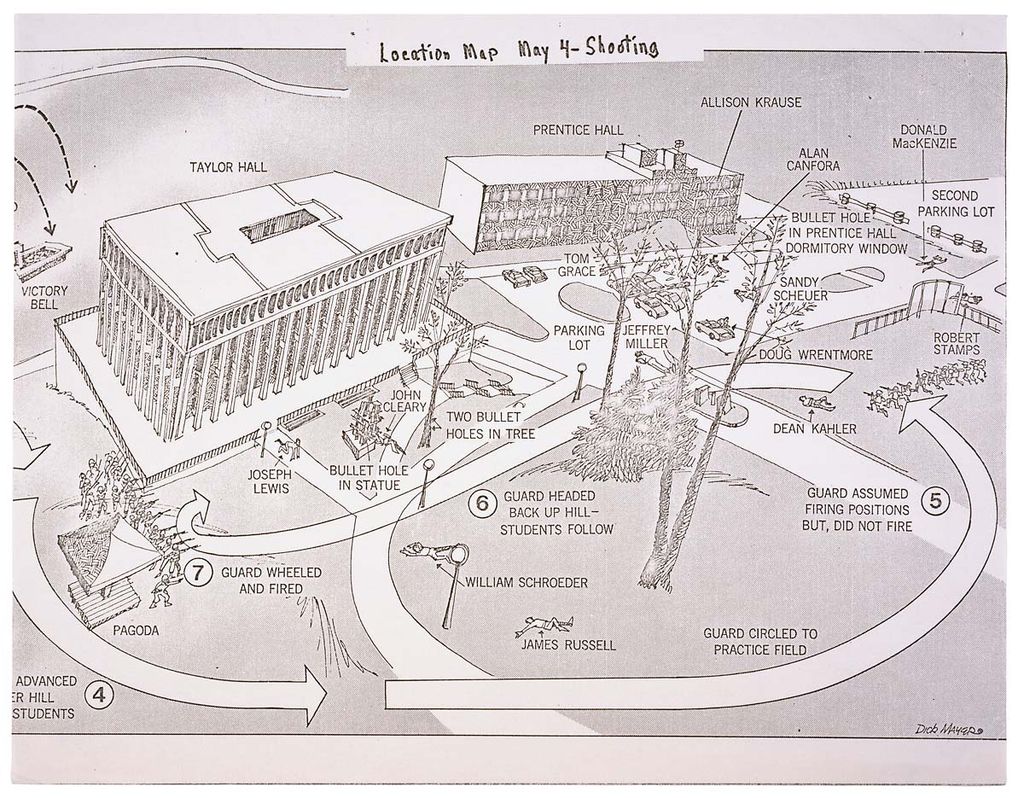

On 4 May, 1970, a large protest had been planned. Despite faculty attempts to convince students the event had been cancelled (by handing out over 12,000 leaflets saying as much), 2,000 people showed up on the campus grounds. The Ohio National Guard arrived and ordered the protesters to disperse, but their messages weren’t able to be heard initially by the massive crowd. Once again, tear gas was used to try to break up the protesters, but several shots fell short, and windy conditions made those that did land close relatively ineffective. Faced with a crowd that was more resilient than usual, the Guard began to advance on the students.

Weapons were locked and loaded, as per protocol, and more tear gas was fired into the crowd at a closer range, forcing the students to retreat. During the advance, though, the Guard managed to get lost on the campus grounds, pinning themselves in a corner. Students assembled, throwing rocks at the guardsmen as they tried to navigate their way out of the situation. Students had moved around them, and many / all but made way for them as the Guard retreated, the protestors following them.

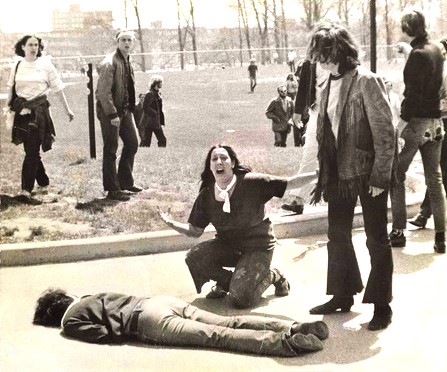

When the guards had retreated up a hill, they turned and fired on the students that were following them, with no warning given. Over thirteen seconds, 67 rounds were fired. Nine students were wounded, and four were killed—Allison Krause (19), Jeffrey Miller (20), Sandra Lee Scheuer (20), and William Schroeder (19). Several eyewitnesses recounted they heard the Guard threatening to shoot again if the crowd did not disperse.

Initial reports were that the National Guard had received several casualties themselves, either killed or seriously wounded. In truth, only a single Guard member required medical attention, receiving a sling for a badly bruised arm.

What followed was one of the largest nationwide student strikes in American history. Over 450 campuses were closed due to protests, with a popular sentiment being “They Can’t Kill Us All.” The Kent State campus itself closed for six weeks, while a similar incident at the University of New Mexico resulted in eleven students being bayoneted by the New Mexico National Guard. A demonstration in Washington D.C., 100,000 strong, degraded to such degrees of vandalism and civil disobedience that the Nixon administration was moved to Camp David.

Nixon himself made a few clumsy attempts at reconciliation, but students and anti-war protestors saw the efforts as trying to save face while Nixon was still under the impression that protestors were under foreign communist influence. The event itself became known as the Kent State Massacre, hearkening back to the Boston massacre, in which five patriots were killed by retreating British soldiers.

The event was a tragedy. Spurred on by a clash of ideologies, rumors, and fear of unrest. The mission of the National Guard that day was not one of protection, but suppression. And I can tell you the difference with a different event. Don’t worry, this one I’ll keep brief.

In 1957, a group of nine black students enrolled in Little Rock Central High School were prevented entry by the governor of Arkansas. Despite the then-recent Brown v Board of Education ruling, which declared the segregation of public schools on grounds of race unconstitutional, Governor Orval Faubus sent in the Arkansas National Guard to prevent their entry, citing rumors of “tumult, riot, and breach of peace.” On this occasion, however, the National Guard did not attempt to force peace through suppression. On the orders of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Guard instead… guarded. Flanking the group of African American students who later became known as the Little Rock Nine, they protected the students from those who would deny them their rights. This event quickly became a cornerstone of the US Civil Rights movement.

Nixon said, “Get rid of the war, there will be another one,” but it didn’t come to pass as he meant it. The use of force and suppression breeds not compliance but retaliation. When protests are shut down, more spring up. The use of force escalates, and people die.

Editor’s Note

While writing the outline for this story, a last-minute press conference was called to the White House on 2 September 2025. One of the items discussed by Donald Trump was confirmation of the deployment of members of the National Guard to the City of Chicago. The stated intention is that they will be working in the capacity of civil law enforcement, much in the same way that they have been deployed in Washington, D.C. and the city of Los Angeles earlier this year.

These are both majority Democrat urban centers that have been pushing back against Trump’s policies, including his use of Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Los Angeles was seeing protests against Trump’s deportation policies, much like Kent was host to protests against Nixon’s expansion of the Vietnam conflict. I can’t say for certain what Trump’s true intentions are for the City of Chicago or how he plans to utilize the National Guard, but, if they are there for the sole purpose of suppressing protests and forcing cooperation with ICE, their directive would be eerily more similar to Kent State than Little Rock.