- Enemies at the ‘Gate

- The United States’ Playground; South America, Pinochet, and Nicolás Maduro

- Enforcing Immigration, Then and Now

By Patrick Dobyns

The last event I’ll be covering that occurred this winter was perhaps the most harrowing sign of what is happening in this country. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agent Jonathan Ross shot and killed US citizen Renée Good. President Donald Trump, a number of federal officials, and ICE have defended the shooting, saying that Ross was acting in self-defense after being run over. Investigations show that this is untrue. ICE had no reason to stop Renée’s vehicle, Renée had no duty to comply, and even if neither of these were true, the penalty for non-compliance is not death. While classification and punishment for this kind of offence vary, resisting arrest in the State of Tennessee can be classified as a Class B or Class A misdemeanor, the harshest punishment for which is no more than 11 months and 29 days in prison and up to $2,500 in fines.

Of course, I can’t write about this without tying it back to history – that’s just what I do. We’ve been talking about the Cold War in previous entries to this series, so it seems apt that we talk about immigration control during the Cold War and how the U.S. defended itself from the tired, poor, huddled masses that threatened our great nation during this troubling time.

One of the first things that should be noted was that formal deportation was a lengthy, complex, and expensive process that depended upon multiple factors outside the control of the Bureau of Immigration. Mass deportation was not possible during this time, as each individual case had to be reviewed and accepted by the nation that would be accepting the deportees. There had been some success in driving out immigrants under what became known as the “Truckee Method,” named after an incident in the town of Truckee, California, where an anti-Chinese “Caucasian League” made life for Asian Americans so difficult and dangerous that the town’s Chinese-descended population, which comprised nearly 40% of the town’s population, voluntarily left the country.

When the U.S. Border Patrol was established, giving the Bureau of Immigration what was essentially an enforcement wing, the Bureau embarked on a campaign of terror, meant to scare the Mexican-American communities of Los Angeles (which, at the time, included families that had resided in the city since before California was a part of the United States) into leaving their homes and “Self-Deporting” to Mexico. In 1931, the U.S. was in the midst of the Great Depression, and job competition was fierce. Anti-Mexican sentiment was high, as workers and unions felt that migrant workers were undercutting prices and taking jobs that U.S. citizens so desperately needed.

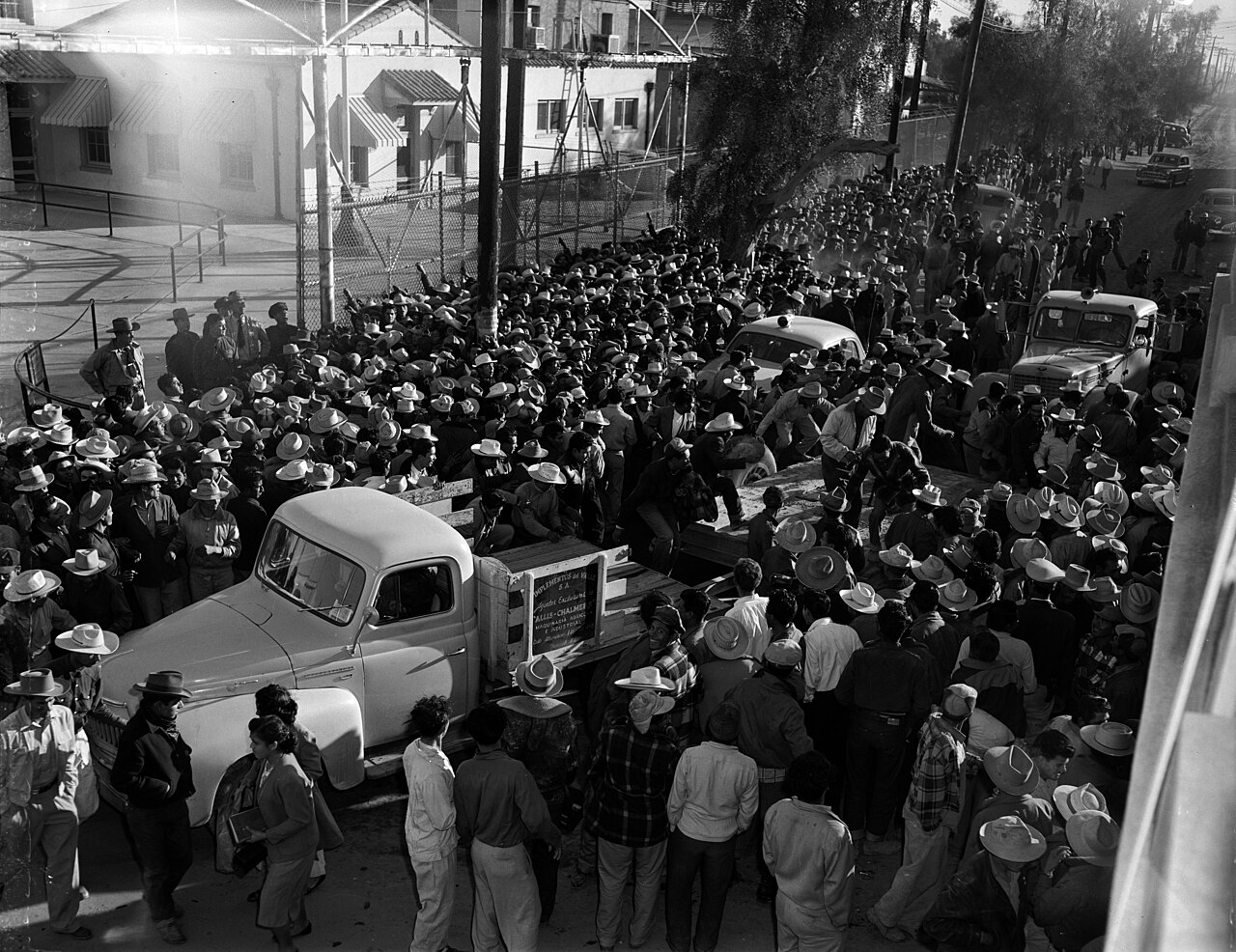

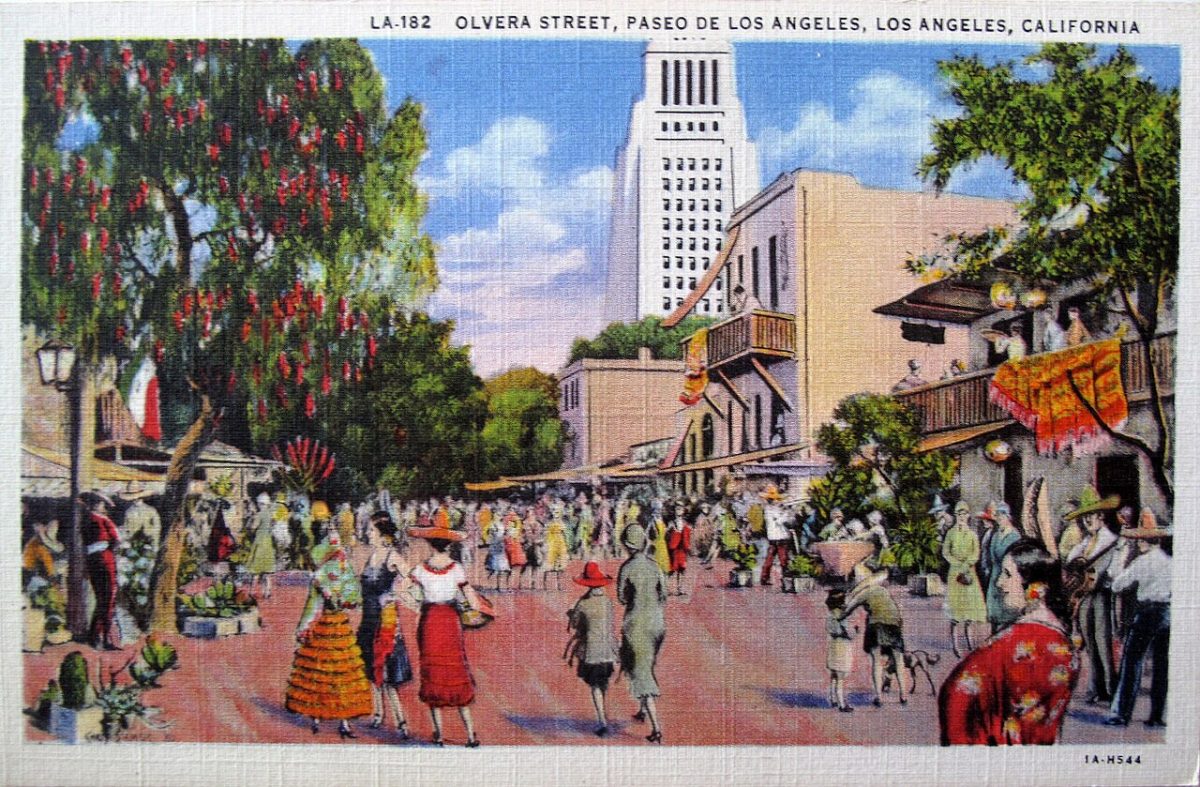

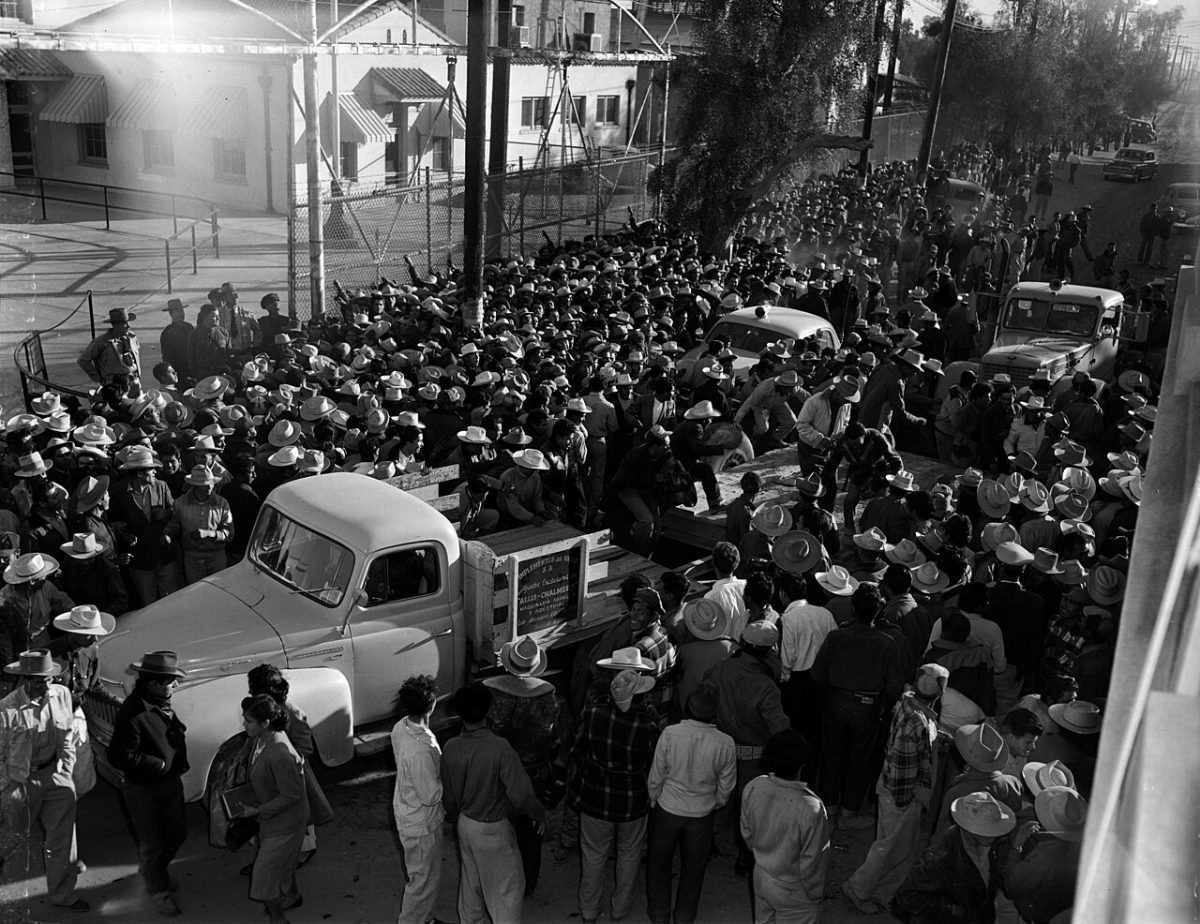

Border Patrol raided La Placita Olvera, one of the oldest Hispanic communities in LA, in February of 1931; officers both in uniform and plain clothes, raided the community and detained over 400 individuals. As this was one of the first immigration raids in U.S. history, many did not have official identification documents on hand.

While it’s not known how many people were deported in this raid, the goal of the raid was not deportation in and of itself. It was a fear campaign, meant to make the Hispanic communities of Southern California fearful of more raids and encourage self-deportation. In 1933, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) was formed as a branch of the U.S. Justice Department and was essentially a precursor to ICE. Their tactics included conducting raids at public and private functions and celebrations in Latin communities and surrounding the areas of operation to catch those who tried to flee, harassing anyone who looked Latin for small offences, and accusing people of illegally crossing the border and encouraging them to self-deport. Throughout the 1930’s, over one million people left Los Angeles for Mexico, some of whom were immigrants and others who were legal U.S. citizens.

There was a dramatic shift in the 1940s, however. As Americans went off to Europe or the Pacific to fight in the Second World War, many left behind agricultural jobs, leaving fallow fields and rotting crops. The government could not risk a food shortage in the midst of the war, so the United States and Mexican governments formed the Bracero Accords. These Accords were essentially an agreement to aid itinerant workers from Mexico to work on U.S. farms, providing the workers with decent pay that would then be spent in Mexico on their return, as the American dollar was a more valuable currency than the Mexican peso. The U.S. government would supply workers with temporary visas and supervise the operations.

The Accords were largely a success and continued after the end of the war, as American soldiers returning from deployment often found jobs outside the Agricultural industry that suited the talents they had acquired in the military. Over 168,000 Braceros worked in the U.S. during the program, and Mexico got a substantial cash infusion. The program did, however, encourage more illegal crossings, as even the flock of applicants could not fill all the needs of the labor market. Many farm owners also saw the payment from the Bracero program to be too generous, forcing them to hire undocumented workers; the government was so desperate to fill in the labor gaps that the INS purposefully overlooked the migrant farm workers.

As the situation continued, however, the Mexican government became more hesitant to allow its citizens to work in the U.S. It emphasized the fact that many Mexicans found working across the border better than in their home country, and it was something of a national embarrassment. Therefore, Mexico began to tighten border restrictions and, when they requested the U.S. to do the same, the INS eagerly complied. Border arrests doubled between 1944 and 1945, and the U.S. and Mexican border patrols began collaborating in order to shuttle deportees further than just dropping them off at the border. Border enforcement began constricting tighter and tighter, with more military troops present and harsher penalties for those caught crossing illegally.

When the Cold War began in earnest, the border “problem” became a political threat rather than an economic one. Stories began to circulate that Mexican immigrants were attempting to flood into the U.S. under a communist agenda, trying to overturn the American way of life. These rumors circulated widely despite the fact that the conservative Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) had a firm grasp on Mexican politics and frequently cooperated closely with the CIA. This “threat” to national security drew the attention of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

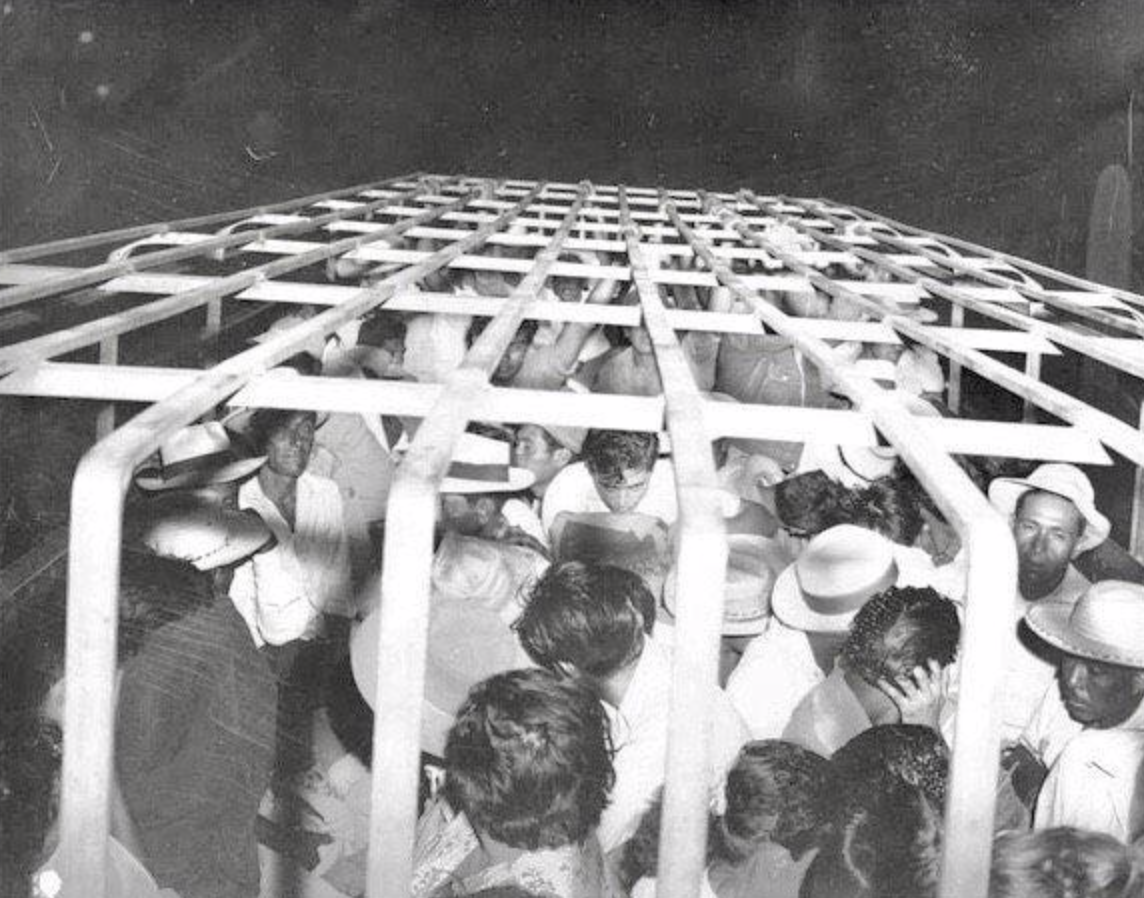

The plan of Eisenhower was based on tactics already in use by Texas Rangers enforcing immigration. A team of heavily armed and highly mobile enforcement agents would scour an area and detain as many people without proper identification as possible, load them up on buses or other forms of mass transportation available to them, and drop them off somewhere in the Mexican interior. Eisenhower and his cabinet began to implement these tactics throughout the rest of the country, with heavy emphasis on states along the southern border but going as far afield as Chicago. This movement was given the absolutely horrendous title of Operation Wetback in 1954, and enforcement agents shuttled migrants across the border via buses, trains, planes, and boats, the latter of which would become infamous for their terrible conditions.

As the U.S. didn’t want to spend a large amount of money using their own ships, the government contracted a few privately owned vessels to carry deportees into Mexico. These passenger ships usually also carried cargo to the United States and, as their passenger decks were reserved for passengers, those being deported were forced to berth in the cargo decks. As cargo did not need to do such things as sleep, eat, stretch, or use the toilet, deportees travelled in cramped conditions with no amenities. These ships were often compared to those that carried enslaved people from Africa during the Atlantic Slave Trade.

It was not just illegal immigrants being deported under these conditions, either. Legal immigrants and American citizens were frequently deported in error if they could not immediately produce legal identification. Chicago saw some of the greatest conflict between citizens and INS, as many of the Hispanic immigrants that settled in Chicago had integrated into the more Americanized community, as opposed to the somewhat insular communities found in places like Los Angeles. When immigrants were detained, it was more likely to be a neighbor or a friend who was being rounded up, so the people of Chicago frequently hid immigrants or encouraged them to go through the formal deportation hearings, which, as previously mentioned, was a more difficult proceeding for the INS to go through.

Public outcry against the inhuman treatment of these people reached a boiling point in late 1955, and the program was ended. Claims from those in charge of the operation put the number of deported at over one million in 1954, but most of these were from well before the operation itself; this exaggeration comes from the use of the fiscal year rather than the calendar year, and the operation only covered the latter two weeks of that time period.

In reality, the number of deportations decreased from the previous year, the operation only having deported around 300,000 people. This is because, once again, deportations were not the goal. The goal was to make illegal entry as risky as possible and encourage legal entry. The Bracero Program was still in effect and still offering visas, and between 1950 and 1956, the number of visas provided in a year jumped from 67,000 to 445,000. The workers could be sponsored by their employers for permanent residency, and the number of legal immigrants jumped from 9,600 in 1952 to 65,000 in 1956. The bait and switch tactics ended up working, as illegal entries declined throughout the 1950’s and encouraged more legal migrations.

Now, what does this terrible operation have to do with the shooting of Renée Good? This article started off by pointing out how she was a U.S. citizen, not an immigrant being deported to Latin America. Aside from briefly living in Canada following the 2024 election, she was born, raised, educated, married, and raised her two children in the United States. So why are we talking about immigration and deportation?

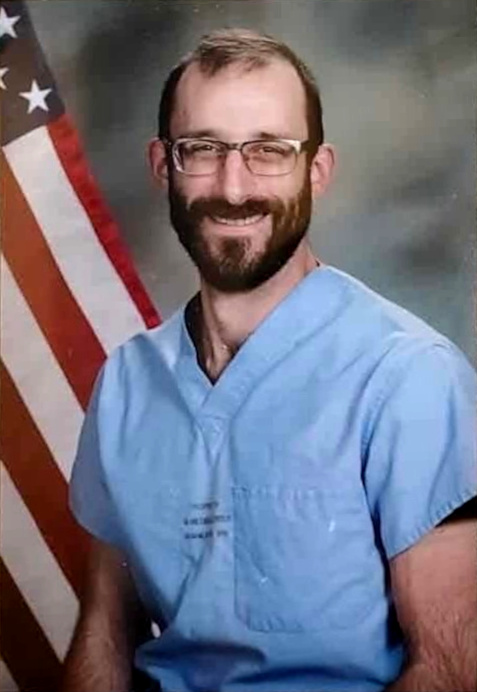

That’s the question, isn’t it? There doesn’t seem to be any logical reason for her to have been stopped, detained, or executed by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents in her home city. The ICE operation, Metro Surge, was originally concocted to investigate the supposed 2020 election fraud and the Somali community of Minneapolis-Saint Paul, a connection supported only by a baseless accusation from the White House. So far, however, a total of 28 people of Somali descent have been arrested, while over 3,400 arrests have been made, according to CBS News. In addition to their 3,400 arrests, ICE agents have publicly killed Renée Good and Alex Pretti, another U.S. citizen who worked for the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

When government-issued statements and hard facts don’t match, it is impossible to ignore. By all appearances, these ICE raids in Minnesota and all across this country are not about immigration. This does not appear to be about keeping the American public safe or ensuring free and fair elections. Although body cameras have recently been issued for all officers, these are still masked officers whose identity is not publicly available who are killing American citizens in the streets and in their vehicles under the direct authority of President Donald Trump. There is a word for what these people are, though it does not exist as a single word in English; in German, that word is Gestapo.

This is why, in November, several Democratic lawmakers sent tweets addressed to U.S. soldiers to disobey illegal orders. This is why protests are gathering more and more steam. We have seen this behavior before. This series of articles has compared the events in US politics that have happened over the winter of 2025-2026 to the actions of the government during the Cold War, but what has been going on in Minnesota is completely unprecedented in American history. Even during the Cold War, there was no such blatant violence against our own people, and the only comparison I can make is either to the totalitarian Soviet government or to Nazi Germany.

One last piece of history for this series: In the years following the Second World War, some of the most heinous and important leaders of the Nazi German government were tried for crimes against humanity and other actions taken during the war. Many pled not guilty, stating that they were simply “following orders” from the state. This became known as the Nuremberg defense because of how frequently it was used during those trials. The International Military Tribunal (with representatives from the Soviet Union, Great Britain, France, and the United States) ruled that this defense was not valid; a person cannot claim innocence of illegal deeds by saying they were complying with orders.