By Bean Gast, Staff Writer

As the digital world rules our reality and political wars surge social media, I find myself desperately looking for a tangible outlet in which to express myself without being criticized. Poetry became my savior, my words a prayer to the God within my soul to summon the hope that lives deep beneath the sorrows of the world. Poetry has reminded me of the power I hold – though I am not the first to make this discovery. That would be the Persians and, more specifically, the Iranians.

It is unfortunate that Iranians live in the shadows of American culture, since their poetry is the light that guides Iran forward during dark times. I can’t help but feel honored that my veins are coursing with Iranian blood, the blood of those who escaped societal standards through the simplicity of verse.

As a young girl, my great grandmother would speak to me in what sounded like Iranian poetry, but really was Farsi. She would say “دوستت دارم” (“I love you”) as she held my face in her hands to say “خیلی زیبا” (“very beautiful”) and though I could not understand her, her words were rhythmic in a way that made me feel loved. Since then, I’ve noticed that Iranians often speak through figurative language and metaphors, which is probably why the words of my great-grandmother, Mehrangez, felt so poetic.

In the pursuit to learn more about Iranian culture and Persian poetry, I had the privilege of speaking with Professor Sara Nezami Nav who teaches ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) classes here at Pellissippi State Community College. Nav was born and raised in Iran in a household that was open minded and encouraging of her dreams to be a theater actress and study Persian Language Literature. After several years of pursuing her endeavors, Nav realized the unfortunate truth that she needed money to survive in this world, leading to her current profession in English Literature.

Our conversation was delightful, insightful, and left me feeling a deeper connection with my Iranian heritage. We discussed many topics surrounding Persian poetry, the first being the origins of Iranian poets, of whom Nav says,

“Generally speaking, Persian poets of different eras had to be mindful of the political and religious hegemonies of their time, often resulting in self-censorship or use of indirect language to navigate potential restrictions and dangers after their work came out.”

A good example of this is Rumi, a 13th-century poet whose work follows the theme of spiritual mysticism and Sufism, an esoteric sector of Islam that celebrates one’s individual union with God. The religion that Rumi wrote about was built on love rather than specific rules or restrictions, even though directly stating his opposition of certain values could result in his execution. The ambiguity of poetry allowed Rumi the freedom to express himself and his words were a shield that protected him from the weapons of his superiors. In The Masnavi of Rumi, he states,

“I am the servant of the Quran, for as long as I have a soul. I am the dust on the road of Muhammad, the Chosen One. If someone interprets my words in any other way, that person I deplore, and I deplore his words.”

Threats of imprisonment and execution were the result of the strict religious order; therefore, Rumi’s statement of his devotion to Islam is an example of the tactics used to protect himself. Protecting oneself through poetry was also present during pre-Islamic Persian, as poetry was originally written to praise the king and spread messages throughout the kingdom. Declaration of shared ideologies to the king was the purpose of poetry at the time and was often a performance with accompaniment of musicians.

Rumi’s broad spiritual values allows for his writing to be relatable to all religions and has prompted his work to be recognized globally while Hafez, a well-known Persian poet from the 14th-century, is only specifically celebrated in Iran. You’d likely find a copy of the Divan of Hafez in nearly every household in Iran due to the cultural traditions surrounding his writing.

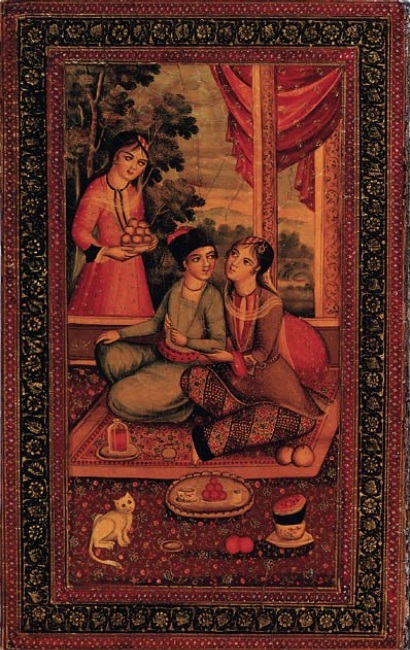

On the longest night of the year, winter solstice, Iranians will celebrate Yalda night with family, food, and poetry. During Yalda night all Iranians and especially their elders will gather to eat nuts and fruits (specifically pomegranates) and read poetry from Hafez. This practice is called Fal-e Hafez; someone will think of a specific goal or wish they have for their future while the book is opened to a random page and the words of Hafez are read. No matter what page you land on, guidance will be provided and your fortune will be told, though it is possible not everyone will be satisfied with their fortune. Fal-e Havez is a tradition that is repeated for several holidays including Nowruz, the Persian New Year during spring solstice.

In order to better understand the significance of Hafez’s writing, I reached out to a local poet, Tatum Scott, who explained that within Hafez’s poetry there are many recurring motifs like the nightingale, the tavern, and wine; each of these are defined in The Illuminated Havez and summarized by Scott.

The Nightingale represents the call to spiritual action and is only heard by those who are awake while the rest of the world sleeps.

The Tavern is synonymous with spiritual community and can be thought of as any place where spiritual seekers gather together to deepen their understanding of truth and to celebrate its intoxicating effects.

Wine represents truth in its distilled form, and the intoxication it produces represents the ecstatic bliss that gushes from the heart once it has obtained spiritual understanding.

Scott writes, “Taking a look at a few of these recurring symbols, you quickly see the common theme—or thread—that weaves all Sufi poems together: the yearning to realize God within one’s own self. It is at this moment of “God /Self Realization” that “Unification with the Beloved” takes place…and the seeker suddenly discovers that their own precious soul was the treasure they had been searching for all along.”

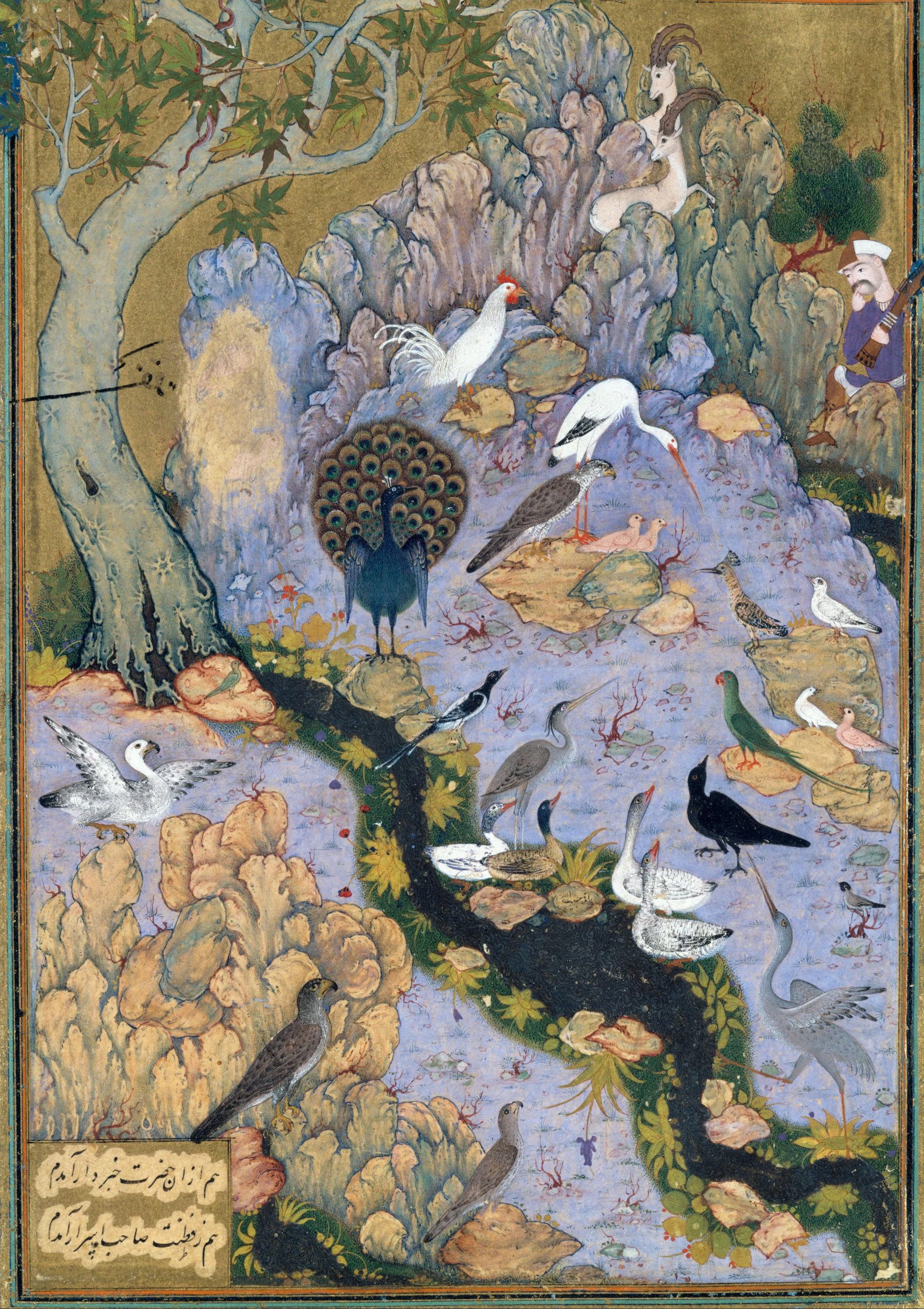

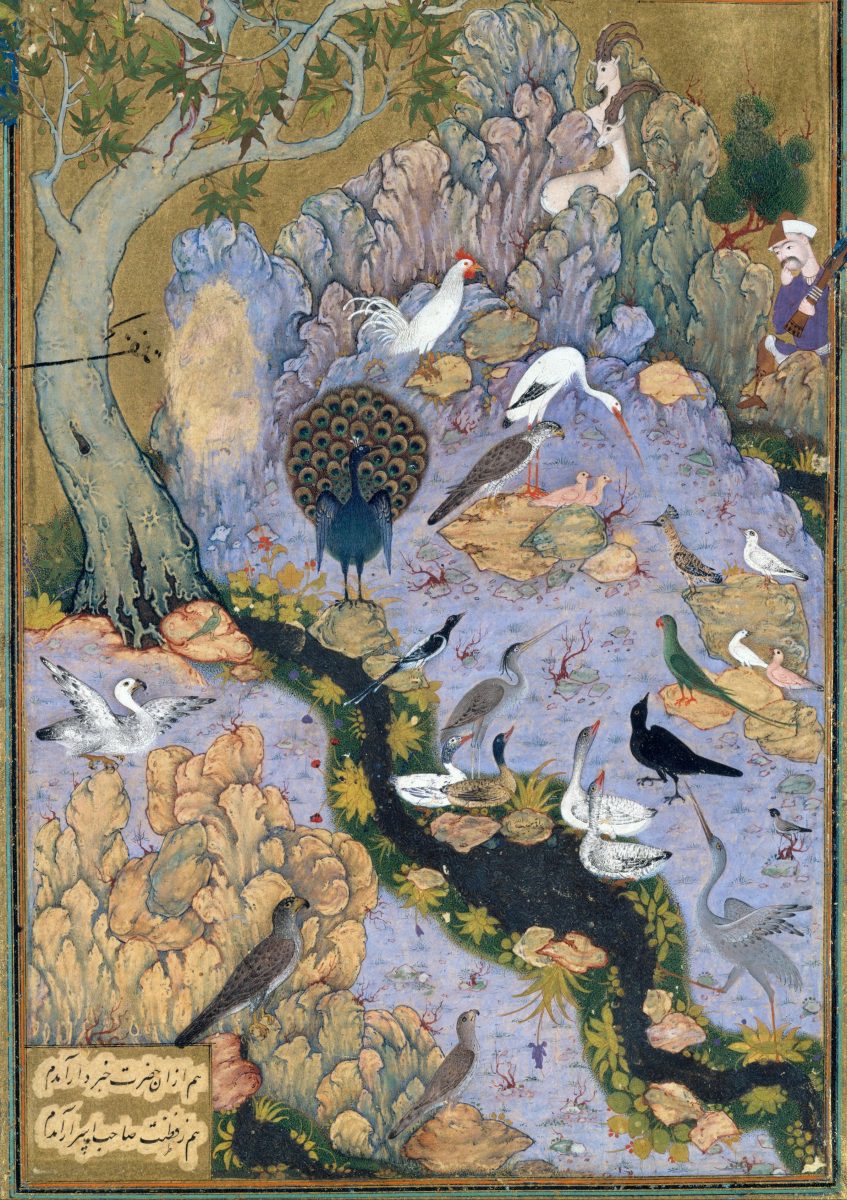

Though Persian poetry is mystic and spiritual, there is also a sector of Iranian poetry that solely teaches a lesson and can be described as “epic poetry.” Professor Nav shared with me her favorite epic by Attar of Nishapur called The Conference of the Birds. Here is a quick summary of the poem (that does not do it justice): a flock of birds led by the Hoopoe, a bird with a feathered crown, travel on a treacherous journey to find their king, the Simurgh, a bird similar to the powerful phoenix. On this journey, they pass through seven spiritual valleys resulting in the injuries and deaths of many of the birds. Finally, they reach the Mountain of Qaf and the Simurgh is nowhere to be found, as the remaining birds see their reflection in the lake and realize that they are the divine entity. The lesson is that through perseverance we can conquer the ego and collectively become the divine, the love, THE God.

Nav says, “All together your collective wisdom is the God. This has been my own view of the world. If you asked me to define God, I would tell you the same story. The more division you have, the less Godly you are. The problem is that people try to find a God outside of themselves, as if the God is out of you, not within you.”

Though I have not read the entire 240 pages of The Conference of the Birds, I deeply resonate with the meaning of the writing, as we hold power together despite our differences. After intently listening to Professor Nav tell the tale, I was eager to hear if she had written any poetry. As she recited her poem from memory, her Farsi brought me back to the times I spent with my great-grandmother and the pure beauty of the Iranian language.

“The Spring” was written by Nav as a 13 year-old girl admiring the nature of rebirth and described as the equivalent to a landscape painting.

”بهاران”

به انسوی جنگلها

سوی کبوتری شاد،

سوی مرغان دریا

گلهای پر طراوت ،

مست و ملنگست اردک

شنا می کند روی آب،

اب زرنگ یک موج زد

قوهای برفی و سفید

می دهند مژده و نوید

که آمده بهاران،

ببار ای خدا باران

شاعر: سارا نظامی ناو

(English Translation)

“The Spring”

Once more I gazed beyond the trees,

toward the joyful dove,

toward the seabirds’ dance,

toward the flowers fresh with love.

A drunken, dreamy duck afloat,

glides gently on the stream

the clever water curls a wave,

and swans of snowy gleam

bring tidings pure and bright,

a promise, soft and clear:

that spring has come again

O God, let rain draw near

I could write pages upon pages about Persian poetry and the power that it holds in the world, in Iran, and in my heart. Though, I feel Tatum Scott summarizes it best, stating

“Persia’s history, values, and aspirations seem to be woven together by a single enduring thread — that being poetry. And it’s through verse that each century found it could bind itself to the next.”

Poetry is the culture of Iran and, although I’m not as familiar with my Iranian heritage as I wish to be, my being is deeply rooted in the verses of poetry. I got the pleasure of speaking with my cousin, Khoosheh Azizbeyglou, who lives in Iran and practices the traditions I described above. She says,

“The digital world keeps people away from thinking [about] who they are and who they used to be. Undeniably, Persian poetry has been surviving our culture and language from distortion.”

We are amidst the depths of the digital age that haunts our reality and disrupts the physical interactions that humans rely on for their survival of joy. Communicating through the aluminum box constantly held in your hand is the very thing disconnecting you from the divine communication of word of mouth. Poetry celebrates the vulnerabilities of humankind and strengthens our differences; poetry will be the God that saves us.