- The Many Origins of Halloween

- Flipping the Coin: A Thanksgiving Play

- Holidays Around the Globe: From Christmas to Yule and Everything In Between

By Patrick Dobyns, Opinion Editor

Unlike Halloween, most of us are likely familiar with the origins of Thanksgiving. We have the story told to us ad nauseum when we go through elementary school and through popular media—the Pilgrims come to America, get blown off course to Plymouth Rock, struggle to survive, and are saved by the generous natives of the region, hosting a feast in thanks. Most of us are also aware of the darker side of the story, how the native people were later treated by English settlers in the region and driven off their own land… if they weren’t simply killed.

Because this story is told again and again and again every year, this time we’ll look at the parts of the play rarely looked at by the audience; those little details too often ignored or overlooked. We’ll look at the who’s, when’s, where’s, and why’s that surround the famous event that took place at Plymouth in 1621.

Dramatis Personae

The Pilgrims

The congregation that would later be called the Pilgrims started as a Separatist movement that split from the Church of England in 1605. While similar to the Puritans, they did not want to alter the church, but simply split away from it. They saw their views and those of the majority of the Anglican church as irreconcilable and did not believe a purification of the church was possible. While still preaching and trying to spread their unique beliefs to the people of England, they were under no impression that their views would ever be in the majority.

The English Crown would not let them preach in peace, however. It was made illegal not to attend Anglican services, and holding separate services could be met with fines or imprisonment. The congregation fled this persecution to a town in the Netherlands called Leiden, where they established a smaller community. They struggled there, having difficulties finding employment, speaking the language, and retaining their congregation. Many of those who had come to the Netherlands ended up leaving shortly thereafter, and those who stayed worried that too many of their children were being influenced by the Dutch.

It was eventually decided that the Pilgrims would relocate to America, despite fears that the settlement process would be dangerous. By this point, most in England had heard the unfortunate tale of the lost Roanoke Colony. The fear of persecution still weighed greater in the Pilgrim’s minds, though, and congregation leaders negotiated for a land patent from the English crown. The Pilgrims were granted the right to settle a piece of land at the mouth of the Hudson River (modern-day New York) on the condition that their faith would not be recognized by the crown.

The Wampanoag

Little is known of the history of the Wampanoag (or Wôpanâak) people prior to European contact. Primarily residing in the lands of what is now Eastern Massachusetts and Rhode Island, they’re thought to have occupied the area for around 12,000 years. They are one of many tribes who practiced what is known as Three-Sisters agriculture — the planting of corn, squash, and climbing beans together — and, while political and warrior roles were taken on by men, property and heredity was passed down by women.

Their first contact with the English had been in 1614, when Captain Thomas Hunt raided the tribes along the southern New England coast and captured some of the native inhabitants. Twenty Wampanoag people were taken from the tribe of Patuxet, including a man named Tisquantum, more often called Squanto. Sold to Franciscan friars in Spain, it was there that he learned English. He escaped by unknown means back to America, only to find his tribe wiped out by disease.

Naturally, this left the Wampanoag with some poor impressions of the English. Tisquantum himself integrated with another nearby tribe, the Pokanokets, and it was here, under the leadership of the Wampanoag leader Ousamequin, that he eventually met the Pilgrim colonists of Plymouth.

Settings

The Mayflower

After briefly returning to England, the Separatist congregation (who now referred to themselves as Pilgrims), in search for a New Jerusalem in America, boarded two ships in London, the Speedwell and the Mayflower. While the Speedwell sprung a leak shortly after its departure that forced it to turn back, the Mayflower and her 102 passengers began her journey across the Atlantic in September of 1620. The ship was not well suited for trans-oceanic travel, however, having only sailed between Britain and France previously. That, combined with the harsh conditions at sea for the season, made the journey far more treacherous than the Pilgrims had anticipated.

The ship sailed in the middle of the Atlantic’s hurricane season, and heavy winds and rain buffeted the ship nearly constantly. Although a popular saying is that the Mayflower landed with one more passenger than it set off with, a child having been born aboard the vessel, that is not true — two people died on the voyage, one of the crew and one of the passengers, while another was nearly lost in the storms, saved from being washed overboard by a thrown rope. The ship also ran out of one of the most critical rations of any ocean-going vessel; beer. When the Mayflower did eventually make landfall, this shortage was a deciding factor in the decision not to travel further South for the intended landing site.

Plymouth

While land had been spotted on November 9, the presumptive colonists did not immediately try to settle it. Firstly, the charter they had purchased was for a plot of land significantly further south than where they were. Secondly, the Nauset people who occupied the area, closely related to the Wampanoag, were immediately hostile to the Pilgrims, shooting at them with arrows and driving them back to the Mayflower.

It wasn’t until December 22 that landfall was made at what would become the Plymouth Colony. The land seemed perfect: a natural harbor was formed along the beach, much of the land had already been cleared, and a series of hills around the clearing provided a good defensive position. It was soon discovered that the reason the area had already been cleared was because they were on the site of an abandoned Wampanoag village, as evidenced by the empty dwellings nearby — many of which still contained the skeletons of those who hadn’t been able to be buried. They had landed on the site of Patuxet, the former tribe of Squanto.

The Story Told, and its Aftermath

From here, the tale of the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag unfolds much as it is often told. The Mayflower Compact was signed by a majority of the men who settled the town, providing a democratic foundation for the future United States; the Pilgrims found they were unable to plant the crops they had prepared; starvation, disease, and the winter weather took many of the colonists; Squanto and Ousamequin saw the struggles of the colonists and taught them how to properly plant the crops which had sustained their people for millennia. The aid was not offered merely from the kindness of their hearts, but as a political gambit, as the Wampanoag were rivals with the Narragansett in what is today Rhode Island. Ousamequin had hoped the English colonists might be able to aid his people against the raids of the other tribe.

Of course, the aid provided to the Pilgrims saved the otherwise doomed colony of Plymouth and, by the harvest season of 1621, the colonists had enough food to observe a common tradition of Thanksgiving. This feast was not the first Thanksgiving, but a tradition common among Puritans and similar religious groups (such as the Pilgrims) which replaced many of the other Anglican holidays. While the Wampanoag were not initially invited to the feast, celebratory gunfire had made the tribe think their new allies were under attack, and many warriors came rushing to their aid fully armed. It was at this point that the natives were invited to partake with the colonists.

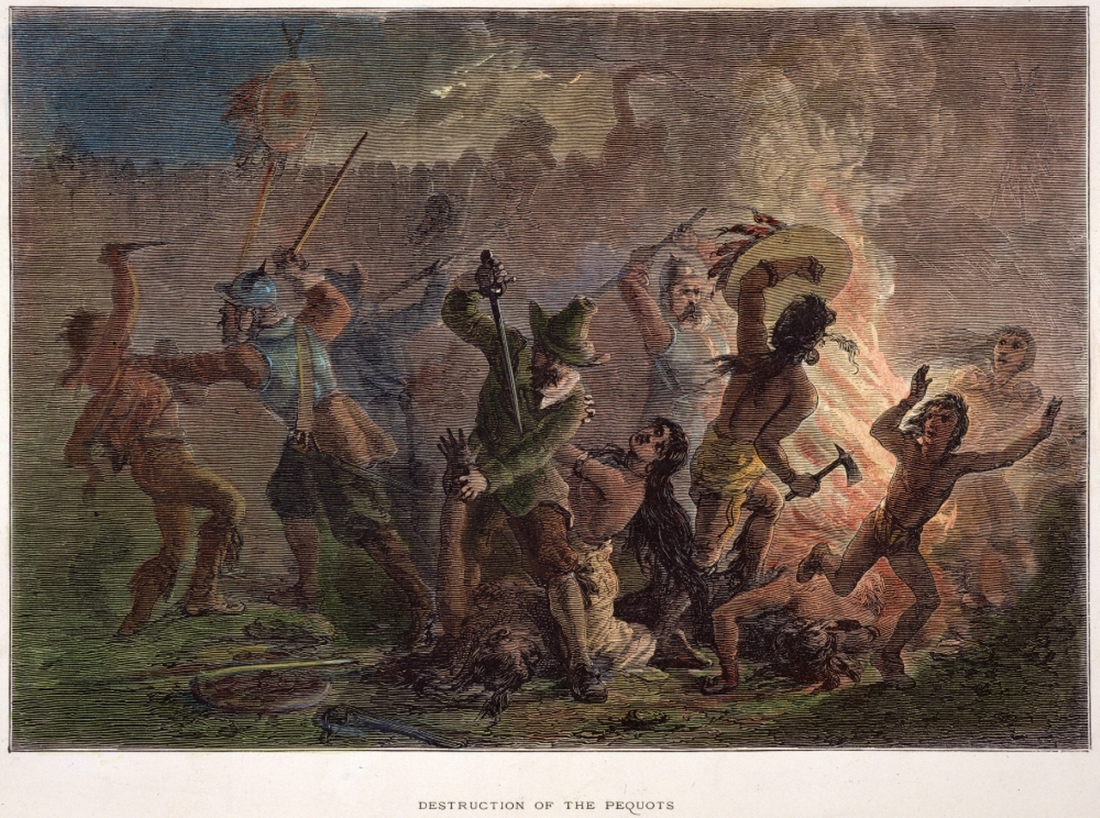

Relations with the Wampanoag and the Plymouth colonists held strong for a long while after that day. English colonies worked with the Wampanoag during the Pequot War, expanding the Plymouth Colony further inland and eliminating a traditional rival of the Wampanoag. When Ousamequin died in 1661, his son, Metacomet, also named Philip, saw relations sour between his people and the English; repeated incursions into his land and colonial retributions against his people led King Philip to lead an armed conflict against the colonists in 1675. While the Wampanoag saw many successful battles and raids, they were ultimately defeated and left without any land.

The Coin

There are two sides to the story of the “First” Thanksgiving. On one side, there is the story of the European settlers and Native American people coming together for mutual aid, sharing in their bounty. On the other side, there is the rest of US history, the repeated abuses and killings of the native people at the hands of European colonists. Because of this, there are many conflicting opinions about Thanksgiving and many questions about how we should celebrate it. Do we remember and mourn what has happened, offering our condolences for the evils that have been inflicted? Or do we celebrate one of the few times we could overlook our differences, where the two sides met to feast and celebrate rather than taking arms against each other?

I myself choose the latter. While we should not — cannot — forget the terrible events of the past, we need to look away from the animosity if we want to move forward in peace. If we want a peaceful example of what we can do working side-by-side, regardless of culture or creed, I can’t think of a better example than that of the founding legend of Thanksgiving.